Understanding Equity % and Tradeable Qty

Equity, tradeable quantity, market cap - what do these numbers actually mean and how do they relate to each other?

Intro

In this post we’ll will describe some of the key numbers Funderbeam provides about the companies trading on the marketplace and show some useful calculations.

The discussion will evolve around price, tradeable quantity, equity and market cap. And how they relate to each other and what we can make of them.

We will be covering main syndicate types - loan notes, share units and the same applies to shares too. They all represent stake in the company1.

Equity %

One of the most important numbers about each syndicate is equity percentage.

Equity percentage shows the stake that each syndicate holds in the investee company. If equity is 10%, the instrument represents 10% of that company’s shares.

This part of the company traded in Funderbeam, the other part is held privately and not traded on public market.

Tradeable part is also called float - because it’s floating, its value can change based on transactions on the secondary market. And those transactions change the perceived value of the company.

The below graph gives a visual representation of tradeable and privately held parts of Funderbeam companies2.

When raising money, startups want to sell as small part as they can for as much money as possible.

(For that matter - investors want to have as big part of the company for as little money as possible.)

Because founders want to give away as little as possible, the typical parts of companies sold and traded on Funderbeam are small - at least compared to huge public companies on big exchanges (see the last to bars on the graph). This is understandable because most of the companies need way more than just one funding round.

Then again, from investors’ and market perspective, the fact that the traded parts are tiny, has its downsides.

As with everything else you buy, you want to make sure you’re getting fair price. But the price of the tradeable instrument alone doesn’t mean anything - you need to calculate the value of the whole company.

As you can see, the price of the whole company is an approximation calculated from the tradeable part. And it’s very different if market value is derived from 2,5% float (in case of Change3) or 29% float (in case of Ampler’s two syndicates).

As equity is percentage and in our cases less than 1, it acts as an “amplifier”. And the smaller it is, the more “amplified” the whole company’s price is.

Let’s look at two companies in which case the value of the float (price * tradeable quantity) are in the same ballpark, but equity differs 7 times:

NB (added 12.07.21): this article uses pre-split numbers for Change as it was written - you guessed - before split.

Are all market cap calculations equal? Here’s a thought experiment:

Imagine 100% of the company traded. Then the denominator in the above formula is 1 and mcap is effectively price * tradeable quantity. If tradeable quantity is 1M, every 1 cent movement will change the company value by 10 000.

At 10% equity, every 1 cent movement will change the company value by 100 000.

At 1% equity, every 1 cent movement will change the company value by 1M.

At (unrealistic) 0,1% equity, every 1 cent movement will change the company value by 10M.

You see the pattern, right? The smaller the equity percentage is, the more affected is the market cap. Tiny changes in share price will amplify big time in company value.

But the formula also contains tradeable quantity.

Tradeable Quantity

When equity shows how big part of the company is traded, tradeable quantity shows into how many pieces that tradeable part is divided. Continuing the previous example from Equity % section - if altogether 10% of the company is being traded on Funderbeam and if the tradeable quantity is 100 000, it means this 10% is in turn divided into 100 000 tradeable pieces. In other words, if you owned all of the tradeable quantity, you’d own 10% of the company.

Based on equity and tradeable quantity, you can calculate how big portion of the company you have by holding one share/share unit/loan note:

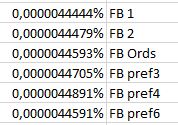

Some examples (smallest and biggest share unit):

If you hold 1 share unit of Change, you hold 0,0000045455% of the company4. This is inconceivably small amount, so let’s see what holding 100 000 share units means - that’s about ~0,5% of the company.

If you hold 1 share unit of CostPocket, you hold 0,0002640127% of the company. Holding 100 000 share units would mean holding 26,4% of the company (which is impossible because the entire float is just 31 400 share units). Holding one unit of CostPocket means you’re holding 58x bigger stake in the company compared to holding 1 Change share unit.

Quick Detour on Voting Rights

This brings us to the argument that some people prefer share units because of the voting rights. Yes, your units have voting rights. But for thought experiment, you might try to calculate the part of any company you actually own and see how small that really is. You can refer to the graph from Equity section to check that none of the companies on Funderbeam offer anything close to majority voting rights.

Previously we argued that the bigger the equity percentage (bigger part of company is traded on Funderbeam), the more accurate is the approximation of company’s market value and how small equity percentage “amplifies” the value more. But let’s take this to the next level.

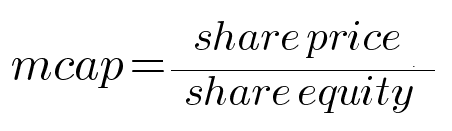

We’ll be using a modified market cap formula in the next part. It can also be derived from the previous formula (from Equity % section) by dividing both numerator and denominator with tradeable quantity.

Either way you calculate it, the formula uses the price from the last trade. If that trade was 1 unit, market value is derived from that price.

That’s right5. The value of 188M company will be actually calculated from 0,0000045455% that is traded. Assume, just for lolz, that the next unit traded for 8,59€.

Boom, mcap changed by 220K (50% owner can claim he’s 110K richer). Go on, try to wrap your head around that.

Update (12.07.2021): After Change 1:3,6 split, the tradeable quantity was increased to 1 980 000 while equity remained unchanged. This means every share unit now represents 0,0000012626% of the company, and every 1 cent price increase changes the company’s market cap by 792 000.

Random interesting fact: 0,0000045455% of Estonia is 2060 square meters or about the size of nice plot to build your house on. Meaning if you compared Change to Estonia, each Change share unit would be equal to 2060 m2 piece of Estonia.

If the above text made a point for big equity percentage, then for the same “amplification” reasons, it might seem like a good idea to have small tradeable quantity too, so that small changes in price get less amplified in market cap.

But let’s try to run some scenarios for different tradeable quantities:

If tradeable quantity was 1, then that share would represent all the stake in the company that’s specified by equity percentage. And that share would be a rarity, meaning there would be no market whatsoever.

If tradeable quantity was 1000, each of the 1000 investors (a reasonable number on Funderbeam) would get 1 share. Better, but still no real market.

At 1M tradeable quantity, 1000 investors will get 1000 units on the average, so they can start trading.

When it might seem like increasing tradeable quantity will create even more liquidity, then you also need to consider the overall valuation and equity percentage - for example if you increased CostPocket’s tradeable quantity from current 31400 to 1M (~32x), then the price of the unit needs to be divided by 32 - it would be ~31 cents instead of 10€. And 1 cent change to 31 cent price will have much bigger effect to overall mcap than 1 cent change to 10€ price.

So, while equity percentage is pretty much fixed by campaign rules, fine tuning tradeable quantity is really the thing that could either enable or kill the market. We say enable because market participants create market, not instrument details. That said, instrument details could have profound effect on the price discovery as we saw earlier.

But there’re one more important aspect you sometimes need to fine tune with tradeable quantity - how multiple instruments relate to each other.

Multiple Syndicates

First of all, let’s consider stock split. What happens during split is that:

You increase tradeable quantity by a factor (say 10), so that if someone held 5 shares, they’re now owning 5 * 10 = 50 shares

You decrease price by the same factor, so if the share price was 50 before, then now it’s 50 / 10 = 5

In other words, each tradeable unit will represent smaller fraction of the company (for lesser price).

And that share of company becomes important when comparing different instruments.

Awhile back Funderbeam had a policy that when releasing new instrument of the same company, it was designed in a way it represented the same part of the company. Quoting their old termsheet:

IMPORTANT: Initial loan note value is EUR 1.19 The initial loan note value has been determined in such a way that a loan note from Funderbeam Syndicate 2 represents the same pro rata share in Funderbeam as any loan note from the previous Funderbeam syndicates (i.e. a loan note from each syndicate represents a similar stake in the startup). This establishes an equal basis for price formation on the secondary market.

Lately, this principle has been tossed out of the window and it’s only possible to compare market cap. So, if everything else is equal, the tokens are priced “correctly” in relation to each other when the respective market cap numbers are equal.

Of course, everything else most likely isn’t equal, there’re always “tiny” details like:

Carry fees (share unit carry fees are settled during campaign, loan note fees are settled on exit, so loan notes should cost less because one has to pay carry fees at some point in the future)

Voting rights - these really cannot be calculated numerically, but as we concluded previously, they’re practically meaningless

Liquidation preferences (Funderbeam’s own units have those)

Examples

Upsteam

Upsteam1 is loan note that has 7,34% equity in the company, divided into 279 730 tradeable notes, so that one note represents 0,0000262396% of the company.

Upsteam2 is share unit with 7,15% equity, divided into 301 772 units, each representing 0,0000236934% of the company.

As you can see, loan note actually represents ~10% bigger share of the company, but has 5% carry fees to be settled in the future, so we can roughly say - not considering voting rights - it should be ~5% more expensive. The market has been quite ineffective here, as in practice the loan note is ~30% cheaper.

Ampler

Ampler1: loan note with 10,93% equity and 409 982 tradeable quantity means 0,0000266597% of the company.

Ampler2: share unit with 18,76% equity and 703 012 tradeable quantity means 0,0000266852% of the company.

Pretty equal, again, not considering voting rights, the loan note should trade at -4% (carry fees) compared to share unit. The market is rather effective here.

Tanker

Tanker loan note: 17,85% equity and 701 061 tradeable quantity mean 0,0000254614% of company.

Tanker share unit: 10,88% equity and 177 820 tradeable quantity make 0,0000611855% of the company.

Here each share unit represents 2,4 bigger stake in the company and trades at 2,6 times the value. Considering carry fees, we conclude it’s pretty fair.

Funderbeam

We don’t really wanna go there. Let’s just say they’re pretty equal from equity perspective6 while pricing is all over the place.

Summary

Why bother with all this math? Because we think it’s always better to understand how things work before making decisions that could cost money. Do you need to know this before starting to invest on Funderbeam? Probably not. We didn’t either.

We don’t think there’s a TL;DR here. But if you didn’t follow our train of thought, we just suggest to use the market cap number that Funderbeam provides both to think about company value and to compare multiple instruments.

But if you found the article interesting, you can either follow Nugis Aino on Twitter or subscribe here to be notified whenever we publish something new:

Those emails, should they penetrate your spam filter, aim for quality rather than quantity. We only say something when we have something to say. If in doubt, you can check also our previous take on Valuation.

If you want to argue that loan note is not stake in company, then please refer to Funderbeam’s own description which says: “In case of a Loan SPV structure, investors always receive a loan note that has the right to any proceeds that arise for the underlying instrument.”

We feel that “proceeds that arise from the underlying investment” would better catch the idea, but the point remains the same.

Data for these graphs here was collected in early May. Some of it changes rarely (equity, tradeable quantity), but some of it more often (number of investors, price and everything that calculated using price - including market cap). So we could be a bit out of date, but that’s not important when explaining the concepts. We also included only companies with mcap > 1M.

While we often use Change as an example of small float - mostly because of its huge market cap - it has to be said that there’re several other companies with <5% float.

After split, this number is 0,0000012626%.

It’s a bit unclear why Funderbeam sometimes arrives at slightly different numbers - whether this is a rounding issue, something in the cap table that we don’t know about or a multiplier which is known to be used in case of Funderbeam 1 and 2 syndicates. They don’t publish the calculation basis, but it’s sometimes impossible to get exactly the same number using public data only.

One theory is that Funderbeam doesn’t round prices to 2 decimal points internally and when dealing with tens or hundreds of millions, these fractions play a role. For example, calculating Change mcap from 11€ and 10.995€ result in 110K difference in mcap.

We’ve also taken into account the following coefficient - quoting their update from 08 Apr 2021: thus one loan note earns the returns generated by holding 0.91417 Ordinary Shares.